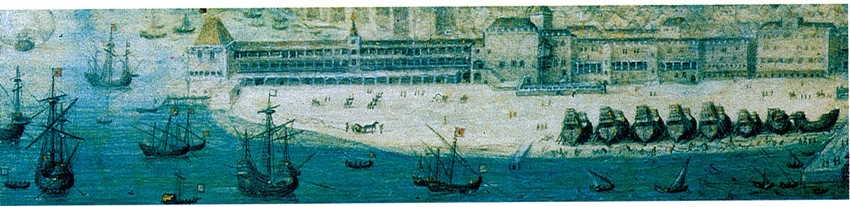

View of the Ribeira Royal Palace c. 1535. Livro de Horas de D. Manuel, fol. 25.Miniature (National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon).

View of Lisbon c. 1730. Departure of S. Francisco Xavier to India (16th century). José Pinhão de Matos (attribution). Oil on canvas (National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon).

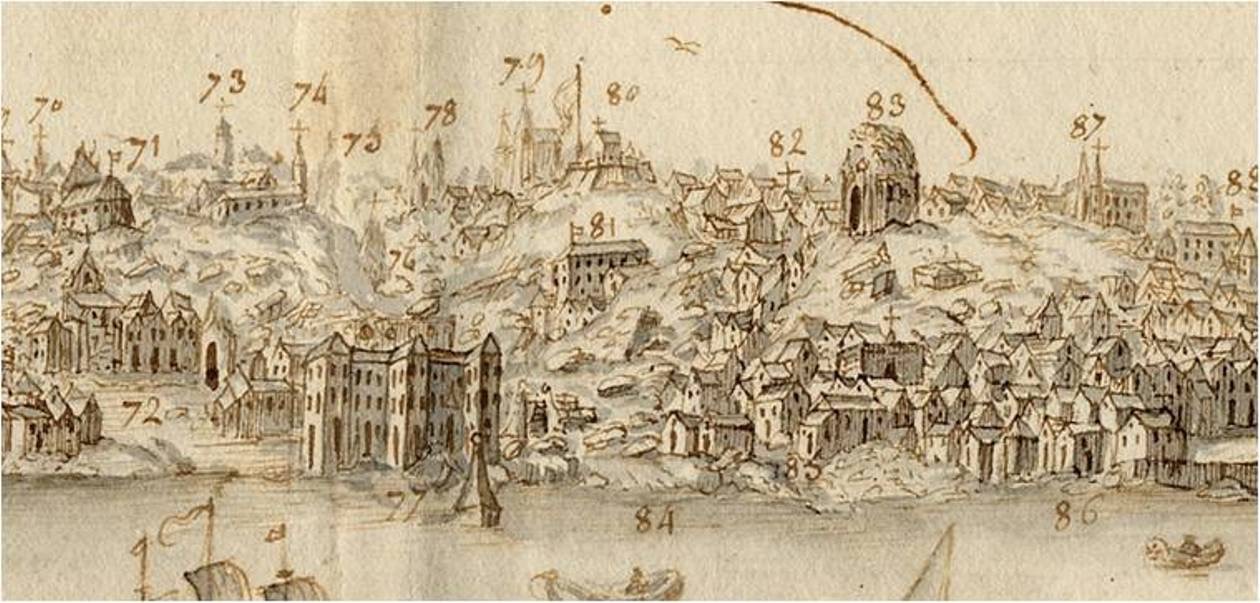

Francisco Zuzarte (attribution). The Palace Courtyard at the eve of the 1755 earthquake (n. d.). China-ink drawing (Lisbon City Museum).

Bernardo de Caula. View of Lisbon ruined by the 1755 earthquake. The Palace Courtyard (detail). Quill pen drawing with sepia and grey ink (National Library of Portugal).

The Lisbon Ribeira Palace (a journey through history)

The primary sources on the history of Lisbon before the 1755 earthquake are scarce and fragmented. A great number of documents were lost in the earthquake. The vicissitudes of the history of Portugal did the rest.

However, the literature on the subject is vast. From the 1980s onwards, the research on Lisbon from an architectural and town planning perspective has experienced a significant boost. Although the earthquake has caused a fracture in the way we view Lisbon’s history, as before and after the event, the lost city is a heterogenous reality. In the last decades, the research has grown in scope and detail, resulting in a deeper knowledge on pre-earthquake Lisbon and its place in the European context.

The Ribeira Royal Palace complex, built at the beginning of the sixteenth century, and henceforth the most noteworthy construction in Lisbon until 1755, has deserved particular attention. The significance of this building and its location in the old Terreiro do Paço (Palace Courtyard) make it an important case-study for the history of Lisbon. The primary sources on the subject are equally sparse. The available iconography is the most illustrative source of information for this complex as well as for the whole pre-earthquake Lisbon. However, it requires careful reading.

The research on this topic crucially needs an all-encompassing approach/tool able to test data, further historical interpretation, extend multidisciplinary work and share the resulting knowledge with a diversified audience.

The museum of the city is particularly relevant in this context. The link between historical research and the IT industry needs to be strengthened. We have today at our disposal several digital tools. They are processing, testing and displaying archaeological data, architectural remains, built heritage, written, iconographic and cartographical sources at a rate and fashion never attained before.

The role humans played in past environments is also an object of active research. This frequently requires a team of artificial intelligence programmers to work closely with historians and archaeologists in order to simulate crowds of humans roaming through a virtual recreation of a historic site. Crowd simulation should be a fundamental part of a research project and not an accessory to the project itself. It provides information on how a historic site might have been used, and allows potential visitors to get a sense of being in a ‘living’ environment as opposed to a static museum exhibit.

Historians actively argue for which options to be made when creating a virtual archaeology project, a departure from the research done in the 1990s, when the goal of the project was usually limited to demonstrating a visual artefact. Rarely the decision-making process was recorded, thus making the task of critically evaluating the 3D model difficult. Methodologies like the London Charter and the Seville Principles suggest frameworks where the focus of the research becomes the detailed process of knowledge acquisition leading to the result, and not the 3D models themselves. Immersive spaces also produce information about the researchers’ interaction with the simulation, which by itself creates new information. Virtual re–creations have become both an instrument and an object of study.

This project aims at using all of their potential to put forward an innovative instrument/laboratory that can be used to study the history of a city and share all of its results to a wide audience in scientific research, education, tourism/leisure and museum communication.